A fast-moving outbreak of Equine Herpesvirus-1 has swept across at least seven states since early November, originating from a major barrel racing event in Texas and triggering widespread event cancellations, interstate travel restrictions, and urgent warnings from veterinary officials. With more than 30 confirmed cases including the severe neurological form (EHM), at least two confirmed horse deaths, and cases still emerging, this outbreak has become one of the most significant equine disease events in recent years. Horse owners must act now—monitoring temperatures, implementing biosecurity measures, and making informed decisions about travel and events during the critical weeks ahead.

The outbreak’s rapid spread underscores the persistent challenge EHV-1 poses to the equine industry: a virus that lies dormant in approximately 60% of horses can reactivate under stress and cause devastating neurological disease in a small but significant percentage of infected animals. Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller has warned that the next two weeks will determine whether the outbreak is contained, while veterinary experts emphasize that disciplined biosecurity—not panic—offers the best protection.

How the 2025 EHV-1 Outbreak Started: Timeline From the Texas Barrel Racing Event

The chain of infection traces back to the WPRA World Finals and Elite Barrel Race held November 5-9, 2025, at Extraco Events Center in Waco, Texas, where approximately 1,000 horses gathered—roughly two-thirds from Texas. No livestock had been on the venue grounds since October 12, suggesting the virus was introduced by an attending horse rather than environmental contamination.

The first confirmed cases emerged on November 18, when the Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) identified horses displaying neurological signs after returning home from Waco. That same evening, the Barrel Futurities of America World Championship in Guthrie, Oklahoma—where many Waco attendees had traveled—was cancelled mid-event after two horses tested positive for EHM on-site.

Within days, confirmed cases appeared in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Washington. By November 25, at least 34 active cases connected to the outbreak had been documented. TAHC confirmed 17 cases across eight Texas counties (Bell, Hood, Wise, Erath, Wharton, Fort Bend, McLennan, and Montgomery) with two horses euthanized. The agency characterized the strain as presenting with “acute progression and high clinical severity.”

However, veterinary experts have pushed back against alarmist narratives. Dr. Ben Buchanan of Brazos Valley Equine Hospitals clarified: “Nothing about this strain is new or makes it more deadly. The reports circulating of 25+ or more equine deaths with at least 200 exposed are inaccurate.” He noted that during the 2011 Ogden, Utah outbreak affecting over 400 horses, only 13 died. The rapid spread in 2025, experts say, reflects the large gathering size and subsequent dispersal to multiple states rather than unusual viral characteristics.

EHV-1 Spread Across Seven States: Current Case Numbers, Quarantines, and Event Cancellations

The outbreak’s geographic footprint continues expanding. Official tracking by the Equine Disease Communication Center shows cases concentrated in the Southwest and extending to the Pacific Northwest, with the highest case counts in Texas (11+ EHM cases), Oklahoma (3 EHM cases), and Louisiana (3 EHM cases). Notably, Maryland and Pennsylvania have reported EHM cases unconnected to the Waco event, indicating independent transmission chains elsewhere in the country.

State responses have been swift. Texas issued 21-day hold orders on all horses that attended the WPRA event, prohibiting movement until December 2 unless symptoms develop. Oklahoma mandated 14-day isolation for exposed horses. Florida suspended Extended Equine Health Certificates and recommended 21-day quarantine for horses arriving from Texas or Oklahoma. Arizona tightened health certificate requirements to 5-day validity periods. Nevada implemented strict entry requirements for horses traveling to the National Finals Rodeo, including 7-day CVIs and entry permits from the state agriculture department.

The National Assembly of State Animal Health Officials took the extraordinary step of suspending Extended Equine Certificates of Veterinary Inspection (EECVIs) nationwide—the 6-month certificates that facilitate routine interstate travel—reverting to standard 7-day CVIs for all movements.

Event cancellations have cascaded through the industry. The National Barrel Horse Association removed sanctioning from all events through December 1. Major cancellations include the BFA World Championship, National Finals Breakaway Roping, Prairie Circuit Finals Rodeo, and the ALL IN Barrel Race in Las Vegas. The NRHA Futurity delayed its start to comply with incubation period guidelines. Regional events from California to Florida have been postponed or cancelled outright.

The Wrangler National Finals Rodeo, scheduled to begin December 4 in Las Vegas, is proceeding with enhanced protocols including mandatory daily temperature monitoring, 7-day health certificates, entry permits, and a no-travel advisory for competing horses before the event.

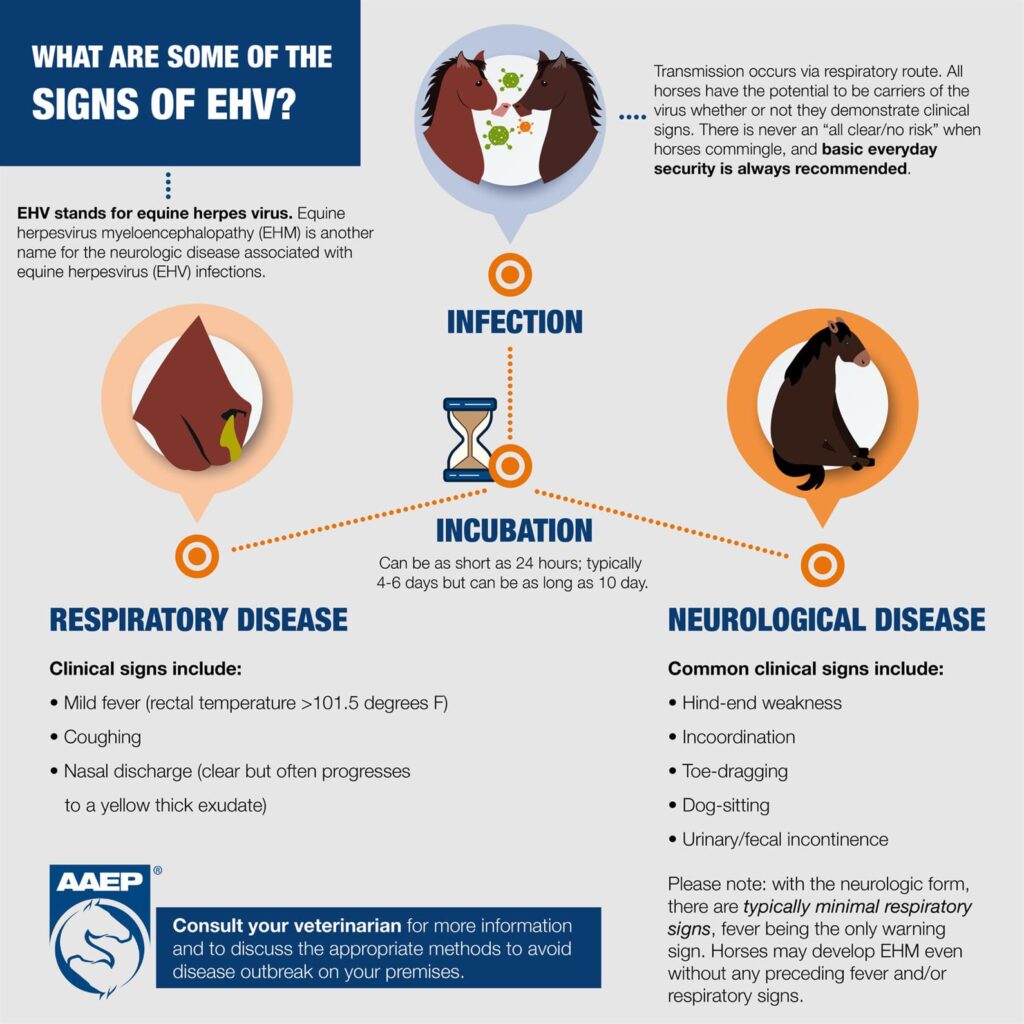

What Is EHV-1? Symptoms, Transmission, and Why the Neurological Form (EHM) Is So Deadly

Equine Herpesvirus-1 is one of the most common viral infections in horses worldwide. According to USDA APHIS, nearly all horses become infected by age two, typically through contact with their dams. The virus then establishes lifelong latent infection in nerve tissue and lymphoid cells, persisting silently until stress—transportation, competition, weaning, or illness—triggers reactivation.

EHV-1 causes three distinct disease forms. The respiratory form is most common: fever (102-107°F), nasal discharge, cough, and lethargy that typically resolves within one to three weeks. The reproductive form causes abortion in pregnant mares, typically between months 7-11 of gestation, sometimes triggering “abortion storms” affecting up to 70% of susceptible mares in a herd. The neurological form, called Equine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy (EHM), is rarest but most feared.

EHM develops when the virus damages blood vessels in the brain and spinal cord, causing inflammation, clot formation, and tissue death. Affected horses develop hindlimb weakness, incoordination, urine dribbling, loss of tail tone, and in severe cases, complete inability to stand. According to UC Davis Center for Equine Health, mortality rates for EHM range from 30-50%, though horses that remain ambulatory generally have favorable prognoses with intensive supportive care.

The critical question—why the same virus causes mild respiratory illness in most horses but devastating neurological disease in others—remains incompletely understood. Research has identified a genetic mutation (D752 in the viral DNA polymerase gene) present in 80-90% of neurological cases. This neuropathogenic strain produces viral loads 10-100 times higher than non-neuropathogenic strains. However, only about 10% of infected horses develop neurological signs regardless of strain, suggesting host immune factors play decisive roles. Older horses appear more susceptible to EHM, though the reasons remain unclear.

Transmission occurs primarily through nose-to-nose contact and respiratory aerosols, effective up to 30 feet. The virus also spreads via contaminated equipment, water buckets, halters, grooming tools, and human hands. Critically, latently infected horses can shed virus without showing symptoms, making them silent spreaders during times of stress.

Early Detection: How Temperature Monitoring Helps Identify EHV-1 Before Neurological Signs Appear

Fever is the most consistent early warning sign of EHV-1 infection, typically appearing 2-10 days after exposure and often preceding neurological signs by 7-12 days. This window creates a crucial opportunity for early intervention.

Dr. Hannah Leventhal of the University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine emphasizes: “For horses returning from affected events, twice-daily temperature checks are one of the most reliable tools we have. Fever often appears before any neurological signs, so identifying that change early allows owners and veterinarians to act quickly and safely. With EHV, time matters.”

Every horse owner should establish baseline temperatures for their horses. Normal adult equine temperature ranges from 99-101.5°F. Any reading at or above 101.5°F warrants immediate veterinarian contact, especially for horses that recently traveled, attended events, or had contact with unfamiliar horses.

Beyond fever, watch for nasal discharge, lethargy, loss of appetite, and swollen submandibular lymph nodes. Neurological warning signs requiring urgent veterinary attention include hindlimb stumbling or weakness, incoordination, urine dribbling or retention, diminished tail tone, dog-sitting posture, or difficulty rising. Dr. Lynn Martin of the University of Missouri notes: “Early signs like a mild fever or nasal discharge might not seem alarming on their own, but they can be the first indicators of EHV exposure.”

Importantly, do not administer NSAIDs (bute, Banamine) to horses under observation for EHV-1 unless directed by a veterinarian—these medications mask fever and can delay critical detection.

EHV-1 Biosecurity Protocols That Work: Proven Stall, Barn, and Travel Prevention Measures

EHV-1 is highly contagious but environmentally fragile. The virus survives up to 7 days on surfaces but is readily destroyed by common disinfectants including diluted bleach (1:10), Virkon S, accelerated hydrogen peroxide products, and quaternary ammonium compounds. This vulnerability makes rigorous biosecurity highly effective.

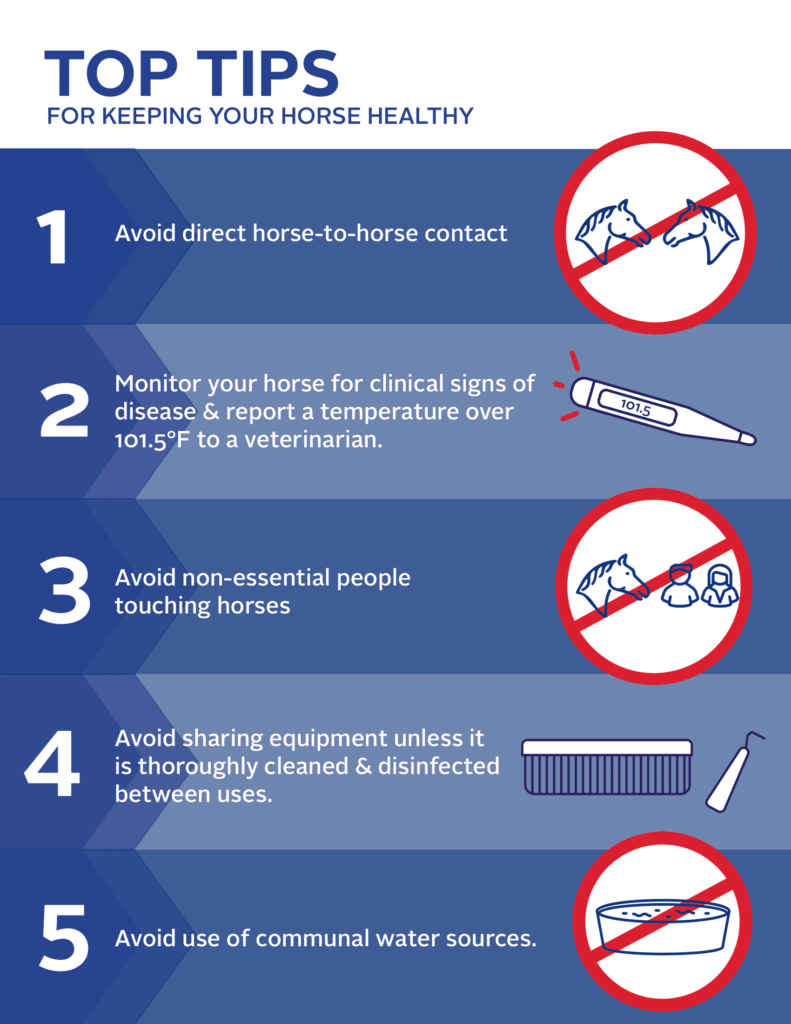

For horses returning from events, implement minimum 21-day quarantine—extended to 28 days for horses returning from affected areas. Physical separation of at least 30 feet (preferably 60 feet) from resident horses prevents aerosol transmission. Use dedicated equipment exclusively for quarantined horses: separate buckets, halters, grooming tools, and thermometers. Handle quarantined horses last in daily routines, change clothes between horse groups, and wash hands thoroughly or use alcohol-based sanitizers.

Facility disinfection requires a two-step approach: first remove all organic material (manure, bedding, debris), then apply disinfectant and allow surfaces to dry completely. Target high-contact surfaces including stall walls, water buckets, hitching posts, and wash racks. Trailers should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected after each use.

For traveling horses, USEF recommends ensuring EHV-1 vaccination within six months of competition, avoiding nose-to-nose contact with unfamiliar horses, never sharing equipment, and maintaining temperature logs throughout travel. Upon return home, immediate isolation and monitoring protocols should begin regardless of whether the horse appears healthy.

During active outbreaks, restrict all horse movement onto and off premises. Cancel lessons, training sessions, and non-essential visitors. Establish boot dip stations at barn entrances and require all personnel to follow strict hygiene protocols.

Does the EHV-1 Vaccine Work? What Vaccination Can and Cannot Prevent in an Outbreak

Current EHV-1 vaccines reduce severity and duration of respiratory disease, decrease viral shedding, and help prevent abortion in pregnant mares. However, no vaccine is licensed to prevent EHM. This limitation reflects the complex immunology of neurological disease, which involves factors beyond simple antibody protection.

Dr. Kile Townsend of the University of Missouri cautions against vaccinating potentially exposed horses: “If a horse was potentially exposed, vaccinating now can cause more confusion than clarity because it can interfere with how the immune system responds during the early stages of infection. For healthy horses with no known exposure, a booster is still a smart step in lowering risk.”

For high-risk horses that travel or compete regularly, AAEP recommends vaccination every six months. Pregnant mares should receive boosters at months 5, 7, and 9 of gestation to protect against abortion. Vaccines require 7-10 days after completion of the series to provide protection, so pre-event boosters should be administered at least two to three weeks before travel. Protection duration is approximately two to three months.

While vaccination doesn’t prevent EHM, Dr. Buchanan notes an important benefit: “Most horses who get sick are able to recover, especially if they have been vaccinated against the disease. The vaccination reduces the circulation of the virus in the horse’s body if they are infected and reduces viral shedding.”

Should You Travel or Attend Horse Events During the EHV-1 Outbreak? Veterinarian Guidance

The veterinary consensus is clear: minimize unnecessary travel and horse-to-horse contact during active outbreaks. Dr. Joe Stricklin, a Colorado veterinarian, advises bluntly: “Stay home. I’m not going to tell anyone to quit living, but this isn’t a common, everyday rhinovirus. It’s a variant that has some deadly potential to it.”

Before attending any event, check current outbreak status through the Equine Disease Communication Center (equinediseasecc.org), your state veterinarian’s office, and relevant breed or discipline organizations. Verify that events are proceeding and understand what biosecurity requirements will be enforced.

If you choose to attend events, implement maximum biosecurity: bring your own water and buckets, disinfect stalls upon arrival, avoid communal wash racks and water sources, maintain distance from unfamiliar horses, and take temperatures twice daily throughout your stay. Upon return, treat your horse as potentially exposed regardless of health status.

For horses that attended the Waco event or subsequent affected gatherings, state veterinarian orders require strict compliance with isolation mandates. Contact your veterinarian and state animal health office immediately if you haven’t already. Do not move these horses to veterinary clinics for routine care—request farm calls instead to prevent potential facility contamination.

Dr. Kelli Kolar, a Montana large-animal veterinarian, summarizes the practical approach: “The biggest thing right now is to just be limiting your horses’ contact with other horses until we kind of get through this outbreak and everything settles down a little bit.”

Final Guidance for Horse Owners: Staying Safe During the 2025 EHV-1 Outbreak

The 2025 EHV-1 outbreak demonstrates how quickly equine disease can spread through the interconnected show and competition circuit, but also how effective coordinated response can be. With prompt temperature monitoring, disciplined biosecurity, and informed decision-making about travel and events, individual horse owners form the front line of outbreak containment.

The neurological form of EHV-1 remains relatively rare—affecting roughly 10% of infected horses—and the majority of those affected can recover with appropriate veterinary care. Panic serves no one, but vigilance is essential. As Texas State Veterinarian Dr. Bud Dinges urged: “Check your horses twice a day, isolate any exposed animals, tighten up your biosecurity, and call your vet the moment something looks off.”

For ongoing updates, monitor the Equine Disease Communication Center at equinediseasecc.org, USDA APHIS at aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/equine/herpesvirus, and your state veterinarian’s office. The next two weeks will determine this outbreak’s trajectory—and every horse owner’s actions today contribute to the outcome.